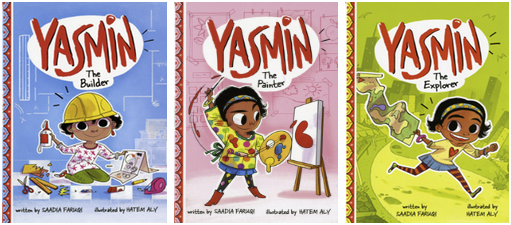

If you haven’t heard of Saadia Faruqi yet, you will soon because she seems to be everywhere at once these days. Her popular early reader series Yasmin has eight books in it now with several on the way, three of which are part of our Individualized Daily Reading (IDR) library; she is the author of the adult short story collection Brick Walls: Tales of Hope & Courage from Pakistan and has two forthcoming middle grade novels; she writes for the Huffington Post and other magazines; she’s editor-in-chief of Blue Minaret, a magazine for Muslim art, poetry, and prose; and she is an interfaith activist, as well as a cultural sensitivity trainer. We’re so happy she took the time to share her thoughts on children’s publishing, writing, activism, and the power of books.

“Books have the power to be the bridge across our cultural divide.”

—Saadia Faruqi

Collaborative Classroom: This quote struck me because literature is the key to our curricula and we too strive to bridge differences by bringing students (and teachers) together in their shared humanity. What in your experience convinced you that books could be the bridge?

Saadia Faruqi: I’ve always found books to be a bridge for me, so it was elementary to assume that this would be the case for everyone. I grew up in a poor household in Pakistan, and the only way I could learn about the world around me was through the books in my father’s bookshelf, which spanned across genres and topics and time periods. Libraries were my haven because the books transported me to other places and allowed me to meet other people, learn about other cultures. Books are often the safest and most accessible way to learn about the other.

“Books are often the safest and most accessible way to learn about the other.”

Collaborative Classroom: One of the reasons we love having Yasmin titles in our Individualized Daily Reading library is that the stories have such an emotionally honest appeal, sharing the everyday worries and triumphs of a creative second-grade girl, who happens to be Muslim. The last fact is not incidental, but it’s not the prime focus either.

Good books like this are rare—ones that focus on Muslim characters and/or non-white life experiences without being historical or issue oriented (and that are written by authors with those very lived experiences). There’s progress, but still a limited number of stories like yours make it through the publishing gauntlet.

Could you speak about your own publishing experiences and what trends you see in the children’s book world at large? Also, could you suggest sources for children’s books about the broad range of Muslim life and culture?

Saadia Faruqi: I agree that there is a huge shortage of what I call “happy stories” about Muslims and many other marginalized groups. The books that get attention are issues books, which are very important, of course, but have the side effect of further marginalizing those groups. If every story you read about a Muslim child or family is one of sadness or grief or injustice, what will you take away as a reader, and what will Muslim children themselves internalize? It’s a very precarious situation, which is why Yasmin and other happy stories like hers are so essential.

I’ve been lucky in that I’ve always found a space for my stories, both issues based and happy ones. I think that mix is very important, so I try to write both. Along with Yasmin I have two upcoming middle grade novels in 2020, one of which is heavily issue based. These books are geared towards older children, who’re possibly going through heavy challenges of being Muslim in the United States.

My own success in writing a variety of stories, as well as watching other authors succeed at it, makes me believe that publishing trends may be shifting slightly. I think overall, marginalized stories—whether in books or movies or television shows—are gaining more traction; they’re getting awards, they’re getting attention. Publishers are businesses, and when they see that marginalized stories, both issues based and not, are making money, the growth trends will continue I believe.

To find sources for books about Muslim life and culture, one has to first understand what that entails. Is there a source for books about Christian life and culture? No, because there isn’t only one Christian culture. Similarly, it’s difficult to find a single source that would list books about all the different cultures and countries that make up the Islamic world. You may find some under African books, others under Middle Eastern, or South Asian. But one place to start researching is lists available on Goodreads, such as “books written by Muslim authors.” Some authors who write about the Islamic world, whatever that means, are Hena Khan, S. K. Ali, and Jamilah Thompkins-Bigelow.

Amina’s Voice by Hena Khan will be included in a forthcoming library as part of our new Collaborative Classroom Book Clubs program, which publishes in 2020.

Collaborative Classroom: When asked “Why Yasmin?” you answered: “When my children began reading independently I saw a need for books that reflected their own realities as dual-culture kids and as first-generation Americans. Being a writer, I decided that if there weren’t books to satisfy those needs, I must write a few.” A few! Happily, there are now more than a dozen titles in print or on the way. You nail the 7-year-old perspective and bring the multigenerational, Pakistani-American family to life with wisdom and a light touch. No small feat for a first-time children’s book author.

On a personal level, how did you leap from “this is needed” to “I will do it”? With regard to the writing itself, how do you pack so much meaning into these short stories?

Saadia Faruqi: That’s how I am. When I see something that’s needed, I get it done. I’ve done it in all areas of my life, so it’s no surprise to anyone who knows me that if I am wondering about something that’s important and needed, I’ll come up with some sort of solution to that problem. Of course this was writing related, so it was an easy jump for me. I was already writing books . . . . I had previously written a textbook and a short story collection for adults, I had published an essay in an essay collection, and I routinely wrote blog pieces and articles for a number of publications. So to write a children’s series when it was what my children needed was almost a natural progression for me.

The Yasmin stories are short, but they always have some sort of lesson or take-away. I credit my editor for helping me a lot with what the story will say underneath all those words. Most people think writing children’s books is easy because they are shorter, but I find it more difficult because you have to say what you want to say in less than 500 words. That can be tough. The other reason why the Yasmin stories can tell so much is the art. Hatem Aly does a fabulous job illustrating this series, and so much is in those illustrations. For instance, in Yasmin the Explorer, when Mama puts on her hijab to go outside, that’s a powerful moment that tells an entire story and teaches so much about Muslim women and how they dress in just one small illustration. There are numerous instances of similar ideas and themes Hatem puts forth due to which the series really shines.

The Yasmin stories are short, but they always have some sort of lesson or take-away. I credit my editor for helping me a lot with what the story will say underneath all those words. Most people think writing children’s books is easy because they are shorter, but I find it more difficult because you have to say what you want to say in less than 500 words. That can be tough. The other reason why the Yasmin stories can tell so much is the art. Hatem Aly does a fabulous job illustrating this series, and so much is in those illustrations. For instance, in Yasmin the Explorer, when Mama puts on her hijab to go outside, that’s a powerful moment that tells an entire story and teaches so much about Muslim women and how they dress in just one small illustration. There are numerous instances of similar ideas and themes Hatem puts forth due to which the series really shines.

Collaborative Classroom: Setting is the foundation of fictional stories, and the setting that shapes our personal stories, our lives, is home. Could you tell us about your childhood in Karachi and your early writing and reading experiences with your family? What was school like and did you have a teacher or mentor who inspired you? If so, how?

Saadia Faruqi: There wasn’t really any encouragement or motivation around writing in my youth. It wasn’t a viable career path so it wasn’t what teachers or mentors even considered. You learned to write well so that it would help in exams or essay writing, or whatever real career you chose. I chose business administration, but my heart wasn’t in it. I read hungrily and constantly, which helped me, I believe, in my storytelling abilities. As I mentioned, my father had quite a collection of books—all old—but varied in terms of content and subject. I read everything from religion to science to philosophy to fiction. We also visited the library quite a bit, both at school and outside, so those all contributed to my literary surroundings.

Collaborative Classroom: What are some ways that your children’s experiences growing up in the United States as Pakistani Americans are different from yours growing up in Pakistan? What do you learn from each other because of these different experiences.

Saadia Faruqi: Everything is totally different. I think a lot of it is also the times . . . Technology for example is so vastly different and hence my kids are growing up with all sorts of experiences I could never have imagined in my wildest imagination! But there’s also the cultural and religious differences. We have to make a conscious effort here to surround ourselves and our children in a Muslim environment, which my parents never had to worry about. I’ve personally put much more emphasis on the religious aspects than the cultural ones. For instance my kids don’t speak Urdu or wear the Pakistani dress, and they’d rather eat American foods than Pakistani ones. And I’m fine with that, because this is their home, not a country they’ve only visited a handful of times. But it’s been a learning experience for me in terms of how their sense of identity and self-worth can be messed up so easily, thanks to our predominant culture and politics. Being a minority child, a person of color, someone from a marginalized group, is really unhealthy for children, and that’s something I worry greatly about not just for my own kids but everyone’s kids. My books are my way of helping correct that.

Collaborative Classroom: Speaking of books, congratulations on branching out into middle grade fiction with two new children’s books publishing in 2020: A Place at the Table and A Thousand Questions. What can you tell us about them?

Saadia Faruqi: Thank you! A Place at the Table is my first middle grade novel, co-written with Laura Shovan and published by Clarion/HMH. It’s a dual narrative about a Muslim girl and a Jewish girl, both of whom are first-generation American middle schoolers who join a cooking club and become friends despite a lot of very serious challenges.

Saadia Faruqi: Thank you! A Place at the Table is my first middle grade novel, co-written with Laura Shovan and published by Clarion/HMH. It’s a dual narrative about a Muslim girl and a Jewish girl, both of whom are first-generation American middle schoolers who join a cooking club and become friends despite a lot of very serious challenges.

This book is really important because it deals with racism and immigration and Islamophobia, but it also showcases very strong cultural elements from both the girls: British and Pakistani.

It’s definitely an issues book, but I have balanced it out with another middle grade novel, A Thousand Questions published by Harper Collins. This is also a dual narrative of two girls—one is Pakistani American and visiting her grandparents in Pakistan, and the other is a servant girl who works at the grandparents’ house. This book also has some serious elements of poverty, corruption, and injustice, but it’s a book where being Muslim is normalized, instead of being the cause of the plot. As I said earlier, I think both types of stories have a place.

Collaborative Classroom: “Even though life itself is different in Pakistan, the emotions and struggles human beings go through, and the hopes and fears they have are the same no matter where they live.” This message of yours resonates throughout all the many kinds of work you do. What stands out to me is that you seem to open minds without judging them for being closed, in essence saying “come along, and I will show you some things you may not know.”

How do you bring such compassion to your activism? What advice do you have for others who are trying to bridge divides, especially when emotions run high?

Saadia Faruqi: It’s really simple. The divide can be bridged only if you get to know the other person. Whether you join an interfaith book club or go on a tour of a house of worship, whether you start talking to your neighbor who may be different from you, it all serves to help bridge that divide, one step at a time. You also have to begin from a place of compassion and open mindedness. It’s difficult, but not impossible, although these are qualities one has to cultivate over time. I always try to remember that inside, we are all storytellers. We all have stories to tell. That’s why I wrote Brick Walls, and that’s why it was so important for me to develop Yasmin and my other work. If we all have stories to tell, then we must also stop and listen to the stories others have to share with us. It has to be a two-way communication, which means really listening to the other person too.

Saadia Faruqi: It’s really simple. The divide can be bridged only if you get to know the other person. Whether you join an interfaith book club or go on a tour of a house of worship, whether you start talking to your neighbor who may be different from you, it all serves to help bridge that divide, one step at a time. You also have to begin from a place of compassion and open mindedness. It’s difficult, but not impossible, although these are qualities one has to cultivate over time. I always try to remember that inside, we are all storytellers. We all have stories to tell. That’s why I wrote Brick Walls, and that’s why it was so important for me to develop Yasmin and my other work. If we all have stories to tell, then we must also stop and listen to the stories others have to share with us. It has to be a two-way communication, which means really listening to the other person too.

“I always try to remember that inside, we are all storytellers.”

I’ve been doing this work since 9/11 so I really know it works. However, it doesn’t work overnight. One meeting with someone different, one online interaction, or one dialogue dinner, however meaningful, won’t make a difference. You have to continue and keep working at it for months, even years. I recently celebrated almost ten years of interfaith dialogue with a women’s book club in my city, and the lessons learned really give me a lot of hope for the future. In fact, there’s an article about it that was published in my local newspaper, the Houston Chronicle.

Collaborative Classroom: Our mission is to help build classroom communities in which every student has a voice and becomes a successful and independent learner. So, moving from the larger community I asked about above to a microcosm of it—school—what advice do you have for teachers who are trying to create a supportive learning environment within a system that perpetuates so many inequities for students of color? Additionally, do you have particular advice for teachers of Muslim students in the United States?

Saadia Faruqi: First and foremost, teachers must educate themselves. Look internally and think about what stereotypes you may already have, what media channels you watch, what understandings you have about Muslims and other marginalized groups and how accurate they are. Many of your interactions may be based on your own assumptions and you may not even know how harmful they can be. So that is really the most important thing. Learn the difference between Muslims from South Asia versus Africa versus the Middle East. We all eat different foods and have different customs and traditions. Some of us are religious, some aren’t. Know that all Muslim women don’t wear hijab, and in fact get educated about what the hijab is because there are so many stereotypes about that. Be there as someone who is kind and loving, because so many Muslim kids—marginalized kids—are facing a lot of bullying from their peers, and many of them have parents who are immigrants and therefore struggling themselves. So being aware of all the complexities of what being Muslim in America really entails—or being any child of color really—that will go a long way in helping the situation.

“Look internally and think about what stereotypes you may already have, what media channels you watch, what understandings you have about Muslims and other marginalized groups and how accurate they are.”

Collaborative Classroom: When describing your collection of short stories for adults, Brick Walls: Tales of Hope & Courage from Pakistan, you said “Every character has a brick wall or obstacle that seems insurmountable to them. Whether that’s an idea, stereotype, or the people around them. . . .”

What has been a brick wall for you and how have you handled it?

Saadia Faruqi: I think for me personally as an immigrant living in the United States, my entire identity tends to be a brick wall. It’s not as much for me, because I came here as an adult with fully formed ideas, but more for others in how they perceive me and interact with me. My hijab may make others uncomfortable; my writing may make them question their own ideas. All these are good things. I always tell my children that challenges are a blessing, because they make us stronger and help us realize our talents and inner strengths.

“. . .challenges are a blessing, because they make us stronger and help us realize our talents and inner strengths.”

ABOUT SAADIA FARUQI

Saadia Faruqi is a Pakistani American author, essayist, and interfaith activist. She writes the children’s early reader series Yasmin published by Capstone and other books for children, including middle grade novels A Place at the Table (HMH/Clarion 2020) co-written with Laura Shovan, and A Thousand Questions (Harper Collins 2020). She has also written Brick Walls: Tales of Hope & Courage from Pakistan, a short story collection for adults and teens. Saadia is editor-in-chief of Blue Minaret, a magazine for Muslim art, poetry, and prose, and was featured in Oprah Magazine in 2017 as a woman making a difference in her community. She resides in Houston, Texas with her husband and children.