Veteran educators Wendy Seger, MEd, and Marisa Ramirez Stukey, PhD, unpack the first of our key topics: what does the research say about the best way to teach foundational skills?

Veteran educators Wendy Seger, MEd, and Marisa Ramirez Stukey, PhD, unpack the first of our key topics: what does the research say about the best way to teach foundational skills?

This blog post is part of an ongoing series, Structured Literacy: Unpacking Nine Key Topics for Transforming Reading Instruction and Outcomes for Readers. (In case you missed it, read the series introduction.)

Does One Size Fit All?

Pretend with us for a minute. This past year, the school board in the town of We-Care decided to support the newcomers to public school in a very special way. They provided each incoming kindergartener with a new pair of well-constructed, durable sneakers.

The sneakers sported a cheerful neon-orange color, heel-activated sparkling lights, and velcro closures. Initially, the students loved the sparkling lights, the teachers loved the velcro closures, and the parents loved the relief to their budgets.

However, there was one major caveat: the sneakers only came in size 12.

The drawback soon became abundantly clear. On kindergarteners with much smaller feet, the shoes were so loose they flopped around and slipped off, sometimes becoming lost. For the children with larger feet, the sneakers were so tight they were painful to wear, and the students began to discard them and go sock-footed or barefoot in the classroom. Recess became a real problem.

In the end, this sneaker program worked only for about one-third of the students—the ones who just happened to fit into a size-12 shoe.

For the other kindergarteners, this well-intentioned support was completely ineffective and a waste of time and resources.

Reflecting on Our Phonics Instruction

This “one-size-fits-all” story seems a bit far-fetched, right? Or is it?

We would contend that in the past, most teachers of reading took the same stance when it came to phonics instruction. Our students all received identical — usually whole-group — instruction.

Given the wide variations in students’ literacy development, “one-size-fits-all” phonics instruction is unlikely to succeed.

And yet, when we consider the reality of a class of incoming kindergarteners, we know that some students come struggling to form their letters and are insecure in most of their sounds.

Meanwhile, others arrive ready for more complex phonetic and lexical knowledge, having figured out or been taught some of the systems of decoding English. Given the wide variations in students’ literacy development, “one-size-fits-all” phonics instruction is unlikely to succeed.

What Does the Research Say?

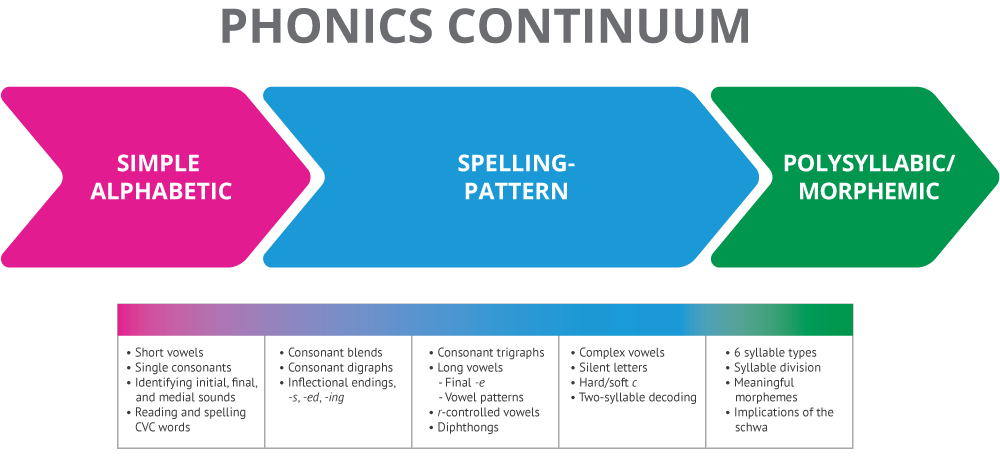

There is a clear path to becoming a fluent reader who decodes accurately and automatically. The path includes explicit instruction on a continuum of foundational skills: the simple alphabetic phase, the spelling-pattern phase, and the more sophisticated polysyllabic and morphemic phase.

Students come to school with a variety of literacy experiences and knowledge about letters, sounds, books, and vocabulary. They can and will enter this continuum at varying points, and our instruction should move them from that entry point on to the next.

Research has shown us that the traditional whole-class phonics lesson is not the way to develop fluent readers—not for kindergarteners or, in fact, for students in any grade level. Whole-class phonics instruction assumes our students all have the same instructional need, but we know this is not the case.

Research has shown us that the traditional whole-class phonics lesson is not the way to develop fluent readers—not for kindergarteners or, in fact, for students in any grade level. Whole-class phonics instruction assumes our students all have the same instructional need, but we know this is not the case.

Whole-class phonics is an “instructional misstep [that] means that fewer children will develop strong word-reading skills. In addition, ineffective phonics instruction is likely to require more class time and/or later compensatory intervention, taking time away from the growth of other important contributors to literacy development.” (Duke & Mesmer, 2019)

Snow et al. (1998, 321) assert that “…intensity of instruction should be matched to children’s needs. Children who lack these understandings should be helped to acquire them; those who have grasped the alphabetic principle and can apply it productively should move on to more advanced learning opportunities.”

Moving from a Data-Informed Position

The first step in providing differentiated foundational skills instruction is moving from a data-informed position. We must use data to determine the students’ instructional needs along the foundational skills continuum, never assuming that all students need to start at the beginning.

Then, we must use this same data to group students for small-group differentiated phonics instruction. In their article, Duke & Mesmer (2019) affirm that “some children are able to develop letter-sound knowledge more quickly and efficiently than others” and advise providing differentiated phonics instruction.

The Importance of a Clear Scope and Sequence

If we consider a continuum of foundational skills instruction to be a progression of more complex skills, we must also follow a clear scope and sequence. A scope and sequence allows us to place students at their instructional points of need, teach in a systematic way, and adjust the intensity of instruction.

As Duke & Mesmer (2019) assert, “across decades, evidence has accumulated to suggest that systematic phonics instruction with a scope and sequence will produce better outcomes than instruction that does not follow a scope and sequence.”

Observing, Assessing, and Responding to Students’ Needs

Lastly, we must respond to the needs of our students. On-going observational and assessment data allow us to respond to the students’ needs and support their word-reading development (Duke & Mesmer, 2019).

Snow et al. (1998, 7) further clarify, “because the ability to obtain meaning from print depends so strongly on the development of word recognition accuracy and reading fluency, both of the latter should be regularly assessed in the classroom, permitting timely and effective instructional response where difficulty or delay is apparent.”

No More “One Size Fits All”: A Vital Instructional Shift

Providing targeted phonics instruction in a small group setting with a systematic process for monitoring learning allows us to be responsive to our students’ needs. We can adjust the pace, frequency, and focus of our instruction, reteaching and reviewing when necessary.

While the shift away from whole-group instruction may be challenging for many of us as educators, it can be life-changing for our students, especially as they encounter the increasing demands of more complex texts in the intermediate grades.

While the shift away from whole-group instruction may be challenging for many of us as educators, it can be life-changing for our students, especially as they encounter the increasing demands of more complex texts in the intermediate grades.

As we plan and prepare for the next school year, we’re wondering how we might score an invitation to speak to the school board at We-Care.

We’d encourage them to let go of their “one-size-fits-all” approach and instead discover how differentiated, small-group phonics instruction provides a more effective way to support all of their students and ensure their success.

***

To learn more about this blog series, Structured Literacy: Unpacking Nine Key Topics for Transforming Reading Instruction and Outcomes for Readers, read the introduction, From Guided Reading to a Structured-Literacy Approach: My Journey as an Educator, by series lead author Kim Still.

References

Duke, Nell K. and Mesmer, Anne E. “Avoiding Instructional Missteps in Teaching Letter-Sound Relationships.” American Educator, 38, no. 4 (Winter 2018–2019).

Snow, C. E., Burns, S. M., & Griffin, P. (Eds.). Preventing Reading Difficulties in Young Children. (Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1998), 321, 7.