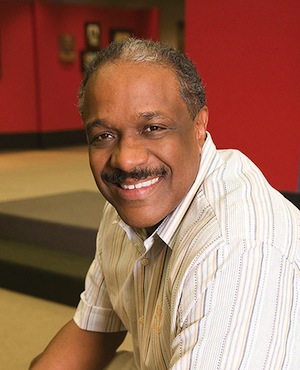

Children’s books are the cornerstone of many of Center for the Collaborative Classroom‘s programs; in a way, the authors are our behind-the-scenes collaborators. We want teachers, administrators, students, and parents to be able to learn more about these wonderful authors and illustrators. We are happy to present the second in our new series of interviews, a conversation with author Christopher Paul Curtis, who transitioned from working on the factory line at General Motors to authoring award-winning children’s literature. His book The Watsons Go to Birmingham is part of our Caring School Community program; Bud, Not Buddy (winner of both the Newbery Medal and the Coretta Scott King Award) is part of our AfterSchool KidzLit program; and Elijah of Buxton (a Newbery Honor Book) is included in our Individualized Daily Reading library.

“I believe when a reader picks up a book, he or she is entering into a contract with a writer, one in which they agree to suspend disbelief long enough and just enough that they can be moved by the artificial construct that is a novel. I hope my readers have faith enough in me to feel I’ve fulfilled my end of the contract with them.”

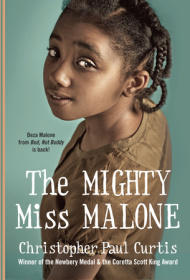

CCC: Humor works hand-in-hand with family to drive the narrative in your books-whether it’s the Watsons’ journey, Bud’s search for his dad, Elijah’s close bond with the Buxton community, or Deza’s determination (in The Mighty Miss Malone) to bring the family back together-affectionate joking runs through even the toughest of times. Could you tell us about your own family when you were growing up? Was there a lot of humor in your home?

Christopher Paul Curtis: I grew up with both parents, a sister who is two years older, a sister who is eleven months younger, a brother who was four years younger, and another sister who is thirteen years younger. And much as in the old saying that there is a thin line between comedy and tragedy, the same can be said about “affectionate joking,” and vicious teasing. There is often a mean-spirited, angry side to poking fun. And while there was plenty of “affectionate joking,” there was also a more sinister, destructive aspect that was common. I don’t think any of my siblings would argue that I was the teaser-in-chief. I thought I was hilarious, unfortunately, no one else in the family agreed. I do believe I came by my teasing sense of humor genetically because I have apparently passed the trait on to my three-and-a-half-year-old daughter who sometimes mercilessly teases her one-year-younger sister. She was recently singing a song and I asked her what it was and she told me she was practicing “The Teasing Song.” Yikes! My sense of humor and any gift of storytelling I have probably come from my grandfathers. Both were great weavers of stories and both were relentless teasers. My father’s father, my Grampa Herman E. Curtis Sr., was a big-band leader and was particularly big on off-color stories. My mother would nearly die when Grampa and I were alone and he’d tell me about being on the road. I was only nine when he died and can only vaguely remember one story dealing with chewing tobacco and spitting it on the hot register of someone’s home. My Grandpa, my mother’s father, and I were much closer and since he lived into his eighties we spent more time together. I can remember how angry my grandmother became with him when she came home and I was in the back yard with a box of salt in my hands. She asked me what I was doing and I told her how Grandpa had told me the way to catch a bird for a pet was to sprinkle salt on its tail. When Gram called me back into the house and confronted Grandpa he told her,

My sense of humor and any gift of storytelling I have probably come from my grandfathers. Both were great weavers of stories and both were relentless teasers. My father’s father, my Grampa Herman E. Curtis Sr., was a big-band leader and was particularly big on off-color stories. My mother would nearly die when Grampa and I were alone and he’d tell me about being on the road. I was only nine when he died and can only vaguely remember one story dealing with chewing tobacco and spitting it on the hot register of someone’s home. My Grandpa, my mother’s father, and I were much closer and since he lived into his eighties we spent more time together. I can remember how angry my grandmother became with him when she came home and I was in the back yard with a box of salt in my hands. She asked me what I was doing and I told her how Grandpa had told me the way to catch a bird for a pet was to sprinkle salt on its tail. When Gram called me back into the house and confronted Grandpa he told her, You gotta give the boy credit for persistence, he’s been out there for two hours waiting to catch one.

One of my biggest regrets is that at the time, I rarely appreciated or cared to listen to the stories they’d tell us.

CCC: I was struck by the character Roscoe’s comment to Deza and Jimmie in The Mighty Miss Malone: “I’ll give you one whole nickel for every joke you find that isn’t cloaked in pain or tragedy.” A joke they never found. You don’t hide the plentiful tragedies in your novels but humor offers a cushion. Tell us about the role of humor in your writing.

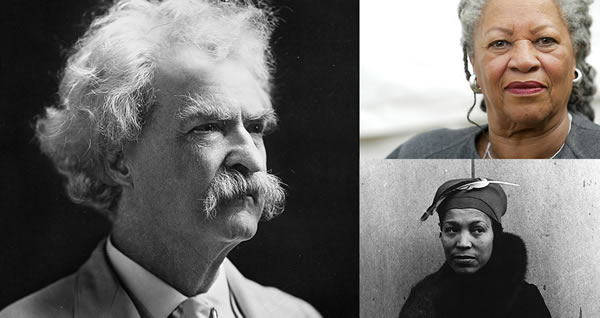

Christopher Paul Curtis: I’m often asked who my favorite author is and the title usually goes to Toni Morrison, Mark Twain, or Zora Neale Hurston. It depends on what day I’m asked and what mood I’m in. I love Morrison for her use of language, for the way I’ll reread a passage she’s written many times and slowly comprehend what she’s doing. I love Hurston for her ability to use deceptive simplicity to pull soaring emotions from me every time I read her. And I love Twain because of his absolute mastery of humor. I believe humor is probably the hardest thing to write and no one has ever done it like Twain. Humor has a very short shelf life; what we laugh at today might not even raise a smile a month or two from now, and a year beyond that it’s totally passé. Unless it’s something written by Mr. Twain; pieces he wrote a hundred and sixty years ago still have the power to reduce me to tears. I can’t tell you how much I admire that power. He suffered so horribly and ached so much because of human foibles that I think he had to develop this gargantuan sense of humor as a counterbalance to pain. This led to his control over humor and its palliative powers. I’m distrustful of criticism and compliments but the compliment that I’m most distrusting of is when something I’ve written is compared to Twain. To paraphrase good old Sam himself, “The difference between Christopher Paul Curtis’ use of humor and Mark Twain’s is the difference between a lightning bug and lightning.”

I believe humor is probably the hardest thing to write and no one has ever done it like Twain. Humor has a very short shelf life; what we laugh at today might not even raise a smile a month or two from now, and a year beyond that it’s totally passé. Unless it’s something written by Mr. Twain; pieces he wrote a hundred and sixty years ago still have the power to reduce me to tears. I can’t tell you how much I admire that power. He suffered so horribly and ached so much because of human foibles that I think he had to develop this gargantuan sense of humor as a counterbalance to pain. This led to his control over humor and its palliative powers. I’m distrustful of criticism and compliments but the compliment that I’m most distrusting of is when something I’ve written is compared to Twain. To paraphrase good old Sam himself, “The difference between Christopher Paul Curtis’ use of humor and Mark Twain’s is the difference between a lightning bug and lightning.”

CCC: An important part of education is having the freedom to take risks and be accepting of potential failure. Sometimes students never begin something for fear of not being able to finish, let alone succeed. Tell us about your elementary school experiences and a favorite teacher, if you had one.

Christopher Paul Curtis: That’s so true. I’ve scuttled many a plan I’ve had because I’ve allowed myself to doubt that I would succeed. It’s a hard trait to overcome and relates to procrastination. Procrastination is based on fear: fear of failure, fear of looking ridiculous, fear of being labeled in some unpleasant way. But if a person is to accomplish anything, this fear must be overcome. I believe small steps to gain confidence are important and I believe that once you can get the self-confidence ball rolling, a lot of barriers will fall. In addition to my parents, there were two teachers at Clark Elementary School in Flint, Michigan, who made me think I could do nearly anything I wanted. The first was my third-grade teacher, Miss Henry. To this day I’m not sure what it is she did to make me feel that way. I mean, I was with her for only four hours a day, five days a week for a mere nine months yet I know she is partially responsible for the path my life has taken. She did recommend me for the gifted and talented program in Flint, but besides that, I can’t think of anything else specific she did. I’m fairly certain she had the same effect on many of my schoolmates.

“My sincerest hope is that those who have chosen teaching as a profession know that theirs is one of the few jobs that can actually break or make another human being.”

Mr. Alums was the second-teacher who came along and helped guide me. He was a no-nonsense, strict, old-school-style teacher who saw something in me and worked to make sure it wasn’t wasted. Once again, if you were to ask me for specifics I couldn’t give any that would be commensurate with this feeling of gratitude and respect I have for these teachers. My sincerest hope is that in addition to the high pay and short hours, the undying admiration of parents and students alike, the three-month-long summer vacations, and the unflagging respect of politicians and bureaucrats around the country, that as a bonus those who have chosen teaching as a profession know that theirs is one of the few jobs that can actually break or make another human being. In spite of the relatively few hours, I spent with Miss Henry (now Suzanne Jakeway) and Mr. Roland Alums they had an impact on me that, 53 years later, is still strong and remembered.

CCC: When did you first think you could write a book? What flipped the switch from writing for yourself (while at General Motors) to sending your stories out into the publishing world? In other words, how did you find your true calling and what advice would you give students about finding theirs?

Christopher Paul Curtis: It’s paradoxical that I didn’t have a lot of self-confidence yet always thought I could be a good writer. As far back as seventh grade I always imagined that, if given the chance, I’d be able to write my way out of anything. I wasn’t driven to write, probably because if I didn’t succeed at it I’d feel terrible, but I can remember being nine or ten years old and telling my brother and sisters, “One day I’m going to write a book and make a lot of money.” It’s burned into my memory because of the many days of “affectionate joking” and vicious character assassination that rained down on me for the ridiculous remark.

“As far back as seventh grade I always imagined that, if given the chance, I’d be able to write my way out of anything.”

I’m only able to speak in general terms when it comes to finding your true calling, as each person and circumstance is so different. But I can say the three P’s seem to be characteristics of people who are fortunate enough to find their way. The three P’s are:

- Patience. This is particularly true for writers. Writing is one of the few arts where life experience is crucial; many young people can write beautifully, they just don’t have anything to say. That comes with patience-waiting to get your butt kicked a time or two gives you a different perspective on life. Know that your writing or anything else you’re aspiring to do will likely improve with time.

- Practice. Self-explanatory. The more you do something the better you’re likely to get at it.

- Persistence. You have to develop a thick skin and be able to look at failures as steps in your journey. Yeah, go lick your wounds, but learn from your mistakes and make the improvements you can.

CCC: A lot of your main characters are risk-takers. Are you?

Christopher Paul Curtis: In some ways yes, in some ways no. I’m the kind of person who is excruciatingly slow to come to taking a risk but once I decide to, I’m all-in. I imagine if you’re not from a factory town or a city that has essentially one industry, it’s very difficult to understand the mind-blowing perceived consequences and risks associated with quitting the job you’ve had for 13 years, as I did at General Motors. A job that pays enough that families of eight lived comfortably off the wages, a job that included benefits and perks that today seem almost utopian, a job whose successful completion required little more than a dogged determination to simply show up every day. In Flint it was as though those who quit the factory hurled themselves into the abyss; the only thing ever heard from them after that being the echoes of their screams of pain, regret, and fear. Someone would quit and months later one of your line-mates would inevitably report, “Yeah, I saw Dennis over on Saginaw Street the other day and, man, did the brother ever look rough!”Yet after 13 mostly unpleasant years spent working in Flint’s Fisher Body Plant No. 1, that’s exactly what I did. (Though truth told, I’d quit emotionally five or six years earlier, it wasn’t until year 13 that GM and I made the separation final and binding.) While it might sound romantic or extremely prescient of me to say I quit because I needed to break free and find my true place in the world (heavy eye rolls here) or that my craft as a writer demanded that I move on from Fisher Body’s drudgery, that simply wasn’t the case. I quit because I was so worn out from the regular nightmares about the factory, or waking up and seeing the door-hanging fixture at the foot of my bed. I was willing to take the risk of quitting because of the serious injuries, physical and psychological, I’d witnessed and experienced. I finally let it go because of an overwhelming desire I had to do anything, anything other than put another damned door on another damned Buick.

“Risks are often taken because the risk-taker has simply run out of other options. That and the fear-or maybe it’s the glimmer of wisdom-that the status quo assures eventual self-destruction.”

I took the risk for the same reason so many other risk-takers do, not some well-thought-out plan to improve myself, not some starry-eyed dream that I have something to contribute to the world, not some brave attempt at a better life. Risks are often taken because the risk-taker has simply run out of other options. That and the fear-or maybe it’s the glimmer of wisdom-that the status quo assured eventual self-destruction. So in many ways my fellow “shop rats” were right; while quitting was taking a risk that I was throwing myself into the abyss, it was a throw that saved my life.

CCC: You’ve created some dynamite male protagonists and in Deza, of The Mighty Miss Malone, you have a spot-on female protagonist. What was it like to write from the perspective of a twelve-year-old girl?

Christopher Paul Curtis: Whenever I try to do something new or different I always seem to set up roadblocks and “what-ifs” that have the effect of sabotaging the effort. This isn’t something peculiar to me; it’s human nature. I struggled with the idea of writing from Deza’s perspective until I had a spell of clear-headed, insightful thinking that hadn’t happened to me in years. I had an epiphany. But to explain the epiphany I have to take a multi-part detour. Part One: Looking back, I see from an early age that I was destined to be a politician. My first political memory was sitting next to my father riding around Flint’s Sixth Ward in our car that had a rented loudspeaker mounted to the top. I was thrilled when Dad let me hold the microphone and repeat, “Vote for Herman E. Curtis for Flint City Council-he’s honest and hardworking!” I really do believe Dad may have won the election if he would have let me say the words I wanted to, “Please don’t hurt us, vote for Curtis!” That had to be the greatest political slogan ever! Part Two: Another sign politics were my future was that from the time I was in fifth grade I would spend every Monday night at seven o’clock with my AM transistor radio tuned to WFDF, the local station that broadcast the weekly Flint City Council meetings. I don’t know why I found these meetings so fascinating but I did. I remember listening to the debates about the Flint fair housing ordinance, a vote that would’ve made it illegal to discriminate against renting or selling a home to African Americans. I remember the tortured logic of the opponents on the City Council (one of whom was actually a civics teacher at the high school I would eventually attend). I remember my anger when the ordinance failed at first. I also remember thinking I would go into politics and start righting all of the wrongs I’d seen and heard about. Part Three: A third part of this epiphany-explaining detour occurred in eighth grade when, for some insane reason, I decided I would run for ninth-grade student government. I remember thinking very methodically about how I’d win. McKinley Junior High was 95% white at that time and firmly planted in one of Flint’s many all-white neighborhoods. There were maybe three black teachers on the staff. I was well aware of this and can still remember reasoning that elections were nothing more than popularity contests. I asked myself: who were the most popular people with students my age? And answered: singers and musicians. I didn’t have time to learn a musical instrument but I did have a passable singing voice (this was right before my voice changed). So, I reasoned, instead of giving the typical boring campaign speech I’d sing mine. Next would be selecting what song to sing. My favorite group at that time was Friends of Distinction but they didn’t have any songs that I could easily use. Plus the white kids at the school probably had never heard of them. The Beatles were extremely popular but if I used a Beatles song I risked losing my African American constituents. I needed a song that was sung by a black artist that got airtime on the white stations as well. I’m not sure how I hit upon “Sunny” by Bobby Hebb but it fit all the requirements.I began reworking the lyrics. I can only remember the first verse but there were eventually three.

Part Three: A third part of this epiphany-explaining detour occurred in eighth grade when, for some insane reason, I decided I would run for ninth-grade student government. I remember thinking very methodically about how I’d win. McKinley Junior High was 95% white at that time and firmly planted in one of Flint’s many all-white neighborhoods. There were maybe three black teachers on the staff. I was well aware of this and can still remember reasoning that elections were nothing more than popularity contests. I asked myself: who were the most popular people with students my age? And answered: singers and musicians. I didn’t have time to learn a musical instrument but I did have a passable singing voice (this was right before my voice changed). So, I reasoned, instead of giving the typical boring campaign speech I’d sing mine. Next would be selecting what song to sing. My favorite group at that time was Friends of Distinction but they didn’t have any songs that I could easily use. Plus the white kids at the school probably had never heard of them. The Beatles were extremely popular but if I used a Beatles song I risked losing my African American constituents. I needed a song that was sung by a black artist that got airtime on the white stations as well. I’m not sure how I hit upon “Sunny” by Bobby Hebb but it fit all the requirements.I began reworking the lyrics. I can only remember the first verse but there were eventually three.

“Voters, just today my life is filled with rain. Voters, your vote for me will really, really ease my pain. Now the dark days will go if you’d just vote for me, From all this pain come and set me free, Voters if you’re true, I need you, Voters if you’re true, I need you.”

After the final two verses, I finally got my chance, I ended by saying, “Please don’t hurt us, vote for Curtis!”Who knows what really happened next? In my memory, there was a long stunned pause followed by a great whooping yell and a very lengthy standing ovation. The teacher who had been running McKinley’s elections since the War of 1812 confided in me that my margin of victory was the largest in any election they’d ever had. I realized I’d had success with writing about boys and since I’m a die-hard feminist I reasoned that there’d be something wrong if I approached the girl’s story in a manner different than I would a boy’s story.

So it was this same type of clear-headed analytical thinking that resurfaced fifty years later when I was worrying myself about whether or not I could write from a girl’s perspective. I broke everything down and took one step at a time. I realized I’d had success with writing about boys and since I’m a die-hard feminist I reasoned that there’d be something wrong if I approached a tale about a girl in a manner different than I would a boy’s story. I knew I had to use the exact same method I used with boys (sitting in the library until a voice came to me, then taking dictation) so I sat until Deza started telling me her story. I’ve also been extremely fortunate in my writing career to have great, supportive editors: Wendy Lamb, Andrea Davis Pinkney, and Anamika Bhatnagar. I had the confidence of knowing if the voice of Deza did veer in an unreal direction, Ms. Lamb would gently nudge it back.

CCC: You have four rules for young writers:

- Write every day.

- Have fun with your writing.

- Be patient with yourself.

- Ignore all rules.

I want to ask you about another one I know you must follow because your novels are powerful examples of it: Show, don’t tell. Time and again you convey a paragraph’s worth of story, character, or background with a simple concrete detail that speaks volumes. How did you learn to do this so effectively?

Christopher Paul Curtis: Thank you very much, but if there is showing-not-telling going on, it’s because I’ve read enough to know what rings true and what doesn’t. I would stress to anyone who dreams of improving their writing that the best way to master any part of the craft is to pick up a book and analyze how an author you admire was able to make you feel a certain way without pulling you out of the moment by overwriting. I think much of what I write is the result of a subconscious application of one thing or another I’ve read before.

CCC: Collaboration and revision are important elements in our Being a Writer program. How do you collaborate with your editor (or with other writers)? Can you describe your revision process?

Christopher Paul Curtis: Revision, collaboration, and then even more revision are the most important parts of writing. That’s true when writing a poem, an essay, a short story, or something as long and complex as a novel. My process is to write my story, constantly and continually revise each section I’ve written, put it all together, read it as a whole, then revise even more. For every hour I spend writing a piece, I conservatively spend ten or twelve hours going over it again and again. What’s bad about this attention to detail is that the process of reading something over and over means I am eventually going to lose perspective as to what the piece is about. A joke may work for the second or third read through, but by the twenty-fifth reading, I guarantee the humor will be gone and there will be a strong temptation to get rid of what may be a perfectly good part of the story. The same with any sort of surprise or mystery I’ve written into the story; after while it’s neither surprising nor mysterious. Here is where the collaboration process comes into play and is a great advantage to the writer. Over the years I have assembled a small group of readers, young and not-so-young, that I trust to be able to give me good feedback as to what is working and what is not. When I am finally convinced that my book is readable, I send it off to these four or five people for their opinions. I cook all of their ideas in my head for a while, then sometimes do and sometimes don’t make changes. It is only at this point that I send it off to my editor to get her input. I often tell young writers that the relationship between a smart writer and their editor is much like that of the relationship of a smart student and a teacher. The wise student or writer knows the teacher or editor is looking at the work from a completely different perspective. We know in some ways the teacher or editor knows more than we do (they are, after all, professionals, and have done this sort of critiquing many, many times) and, since they are looking at the piece with fresh eyes they will know what is funny, what is mysterious, and what is surprising. They’ll also know what just plain stinks and, hopefully, can gently make the student/author aware of this. What’s good about me reading and revising a piece many multiples of times is that it allows me to be proud of what I’ve written. It will be my name on the paper or the book when I’m done and I want to be sure I can live with the end product.

CCC: You do such an excellent job bringing history to life in a way that’s relevant for young people. How do you select the historical events and settings that are the foundation of your novels? What inspired your interest in history?

Christopher Paul Curtis: The expanded version of my second rule for young writers is “Have fun with your writing because as a writer you have almost god-like powers.” You can create and destroy whole universes. You can give birth to some of the most remarkable human beings ever and if they become unpleasant, unmanageable or a little too sassy, you can snuff them out at your slightest whim. You control everything; enjoy that feeling while you’re writing because it sure ain’t about to happen in your real life. That’s the way I approach exploring an event or a historical era. Even with that in mind, it’s always difficult for me to determine where the inspiration to write about a particular event came from. If I’m going to invest a year or two in writing about a specific time, one prerequisite is that I must have some lingering questions about what happened historically. Examples of this appear in Bud, Not Buddy and The Mighty Miss Malone and take place in the “Hoovervilles” described in those books. My first introduction to John Steinbeck’s work happened through the movie The Grapes of Wrath. I think the depiction of the homeless camps in the movie (and subsequently in the book I borrowed from the library) had a profound effect on me. I saw these places as great representations of what can be the best of human nature. People recognized the need to care for one another, to work toward maintaining peace and to understand the sense of a shared destiny. I wanted to look more closely into this and thus, as only a writer can do, I set part of my story there. Another reason history has fascinated me is, as earlier discussed, that I’m able to take a look at an event from a nonstandard perspective. There are at least a couple of reasons that historical fiction for young readers provides the perfect platform from which to answer those questions or launch that new look; first, the age of the narrator. After much trial and error, I’ve discovered my sweet spot for a first-person narration is ten years old to the earliest teen years. That age span seems to serve as a sort of resting spot in our march toward some modicum of human maturity. It’s almost as though we take a breather in going from being a person who is learning to master our own thought and body processes, to the time when the disease of adolescence kicks in and we lose all touch with reality and slip perilously close to being something not quite human.

Christopher Paul Curtis: The expanded version of my second rule for young writers is “Have fun with your writing because as a writer you have almost god-like powers.” You can create and destroy whole universes. You can give birth to some of the most remarkable human beings ever and if they become unpleasant, unmanageable or a little too sassy, you can snuff them out at your slightest whim. You control everything; enjoy that feeling while you’re writing because it sure ain’t about to happen in your real life. That’s the way I approach exploring an event or a historical era. Even with that in mind, it’s always difficult for me to determine where the inspiration to write about a particular event came from. If I’m going to invest a year or two in writing about a specific time, one prerequisite is that I must have some lingering questions about what happened historically. Examples of this appear in Bud, Not Buddy and The Mighty Miss Malone and take place in the “Hoovervilles” described in those books. My first introduction to John Steinbeck’s work happened through the movie The Grapes of Wrath. I think the depiction of the homeless camps in the movie (and subsequently in the book I borrowed from the library) had a profound effect on me. I saw these places as great representations of what can be the best of human nature. People recognized the need to care for one another, to work toward maintaining peace and to understand the sense of a shared destiny. I wanted to look more closely into this and thus, as only a writer can do, I set part of my story there. Another reason history has fascinated me is, as earlier discussed, that I’m able to take a look at an event from a nonstandard perspective. There are at least a couple of reasons that historical fiction for young readers provides the perfect platform from which to answer those questions or launch that new look; first, the age of the narrator. After much trial and error, I’ve discovered my sweet spot for a first-person narration is ten years old to the earliest teen years. That age span seems to serve as a sort of resting spot in our march toward some modicum of human maturity. It’s almost as though we take a breather in going from being a person who is learning to master our own thought and body processes, to the time when the disease of adolescence kicks in and we lose all touch with reality and slip perilously close to being something not quite human.

CCC: Reading an excerpt of your essay about leaving factory work, I found the same great insight and humor you display in your kids’ books (“It was one thing to get hit by a car and killed coming into work; it was a whole different level of tragedy to get nailed on the way out after having given your last nine-and-a-half hours to General Motors.”). How did you decide to write for children? Have you ever considered writing books for adults?

Christopher Paul Curtis: Even though it smacks reality in its face, I’ve never really considered myself a writer for young people. When I was writing my first book, The Watsons Go to Birmingham-1963, I thought of it as a story being told by a ten-year-old boy; I never considered ten-year-old boys to be my audience. Truth told I don’t consciously think of my audience at all when I’m writing. I’m writing to myself. Now I’m aware that my books have found a home with young people and of course, I’m conscious of that fact, but I try not to let that influence the writing. In fact, early in the process, I’ll write in the voice of a sixty-something man from Flint, Michigan, (my own voice) just so I can get the flow of the story going. It’s only once I’m comfortable with the voice I’m telling the story in that I translate what I’ve written to be a more apropos youngster’s voice. I have had a book for adults on the back burner for twenty years. It takes place in Flint during the early seventies to mid-eighties and is centered around factory life. There are alternating narrators: one a pot-head sweeper who is hustling his way through life and the other a very young man who feels he has trapped himself in the factory. I’ve got a couple hundred pages done so I’ve invested a lot in it, but to put a different spin on an old commercial, “It isn’t soup yet.” One of the reasons I haven’t finished it is because the language of the writing is very different from what I usually write, and while I find it easy to work on two different books for young people at the same time, I’ve found it impossible to do so with doing an adult novel and a middle reader concurrently. The voice for the adult book is much raunchier and raw, vulgar even, and going from that to the voice of a ten-year-old has been problematic. One day I’ll devote the time to finish the story, but not for a while yet.

“My effort, and the efforts of many other writers of fiction for young people, is, to paraphrase Jacqueline Woodson and Rudine Sims Bishop, to simply hold a mirror so that I can reflect the readers’ faces back onto them and point out a window so the “others” can look through and see we’re not so frightening after all.”

CCC: What was it like for you in 1995, as an African American man writing realistic stories about African American families in the very white realm of children’s book publishing? How has (or hasn’t) the industry changed over the course of your career? In 2000 you were the first African American man to win the Newbery Medal (first awarded in 1922). How did that change your life?

Christopher Paul Curtis: It never occurred to me in 1995 that I was “writing realistic stories about African American families in the very white realm of children’s book publishing.” But that’s a pretty apt description of what I was doing. It’s good that I wasn’t thinking in those terms because I might have realized what a daunting task that would be and I might have waved the white flag. Unfortunately, twenty years later, it’s still a daunting task. Despite sincere efforts on many fronts to make the publishing world more inclusive and a better reflection of our world, there is a dearth of novels for, by, or about anyone other than the white mainstream. But that’s not something that is exclusive to publishing; it’s the great Gordian knot of American history. My effort, and the efforts of many other writers of fiction for young people, is, to paraphrase Jacqueline Woodson and Rudine Sims Bishop, to simply hold a mirror so that I can reflect the readers’ faces back onto them and point out a window so the “others” can look through and see we’re not so frightening after all.

CCC: What do you hope your readers will know or feel when they finish one of your books?

Christopher Paul Curtis: My biggest hope is that my younger readers will feel a sense of curiosity when they finish one of my books. I hope I’ve piqued their interest in whatever I’m writing about and that will lead them to further investigation of the subject. Ideally, they’ll seek out a nonfiction book and see where my story sits historically. With readers of all ages, I think it’s crucial that they be entertained and feel empathy with my characters. Writing is a grand act of manipulation, and writers have so many tools at our disposal to influence readers. We have time. We can go over something again and again until we get it as close to right as we can tolerate. We have access to great books that have come before, which are storehouses of knowledge of craft. We have access to older, wiser human beings who are a treasure of minute historical details. There is a saying that with the death of every senior the world loses another library. If we act quickly enough, writers have access to those libraries. We have access to our own experiences and we have the fact that these experiences are filtered through the prisms of our lives, which make the story our own. With all of that working for me as a writer, with all of those tools on my side, I hope most of all that my readers enjoy the stories and learn something to boot. I believe when a reader picks up a book, he or she is entering into a contract with a writer, one in which they agree to suspend disbelief long enough and just enough that they can be moved by the artificial construct that is a novel. I hope my readers have faith enough in me to feel I’ve fulfilled my end of the contract with them.

Writing is a grand act of manipulation, and writers have so many tools at our disposal to influence readers. We have time. We can go over something again and again until we get it as close to right as we can tolerate. We have access to great books that have come before, which are storehouses of knowledge of craft. We have access to older, wiser human beings who are a treasure of minute historical details. There is a saying that with the death of every senior the world loses another library. If we act quickly enough, writers have access to those libraries. We have access to our own experiences and we have the fact that these experiences are filtered through the prisms of our lives, which make the story our own. With all of that working for me as a writer, with all of those tools on my side, I hope most of all that my readers enjoy the stories and learn something to boot. I believe when a reader picks up a book, he or she is entering into a contract with a writer, one in which they agree to suspend disbelief long enough and just enough that they can be moved by the artificial construct that is a novel. I hope my readers have faith enough in me to feel I’ve fulfilled my end of the contract with them.